Seven years ago, Jayden Cummins went to his local chemist to get something for man-flu. The chemist said he didn’t look well and suggested he see a doctor. The doctor said he had a heart arrhythmia and sent him to hospital. After a barrage of tests at his local hospital, he was told he had 48 hours to live. Heart failure kills 45,000 Australians every year and it’s the leading cause of death worldwide. Jayden was as sick as a human can be, but waking up in St Vincent’s after being transferred here on life support, he was one of the lucky ones.

St Vincent’s hospital is a world leader in heart and lung transplantation, and the work of St Vincent’s Centre for Applied Medical Research (AMR) is helping more eligible patients not only live long enough to receive a transplant but enjoy an improved quality of life while they wait for one.

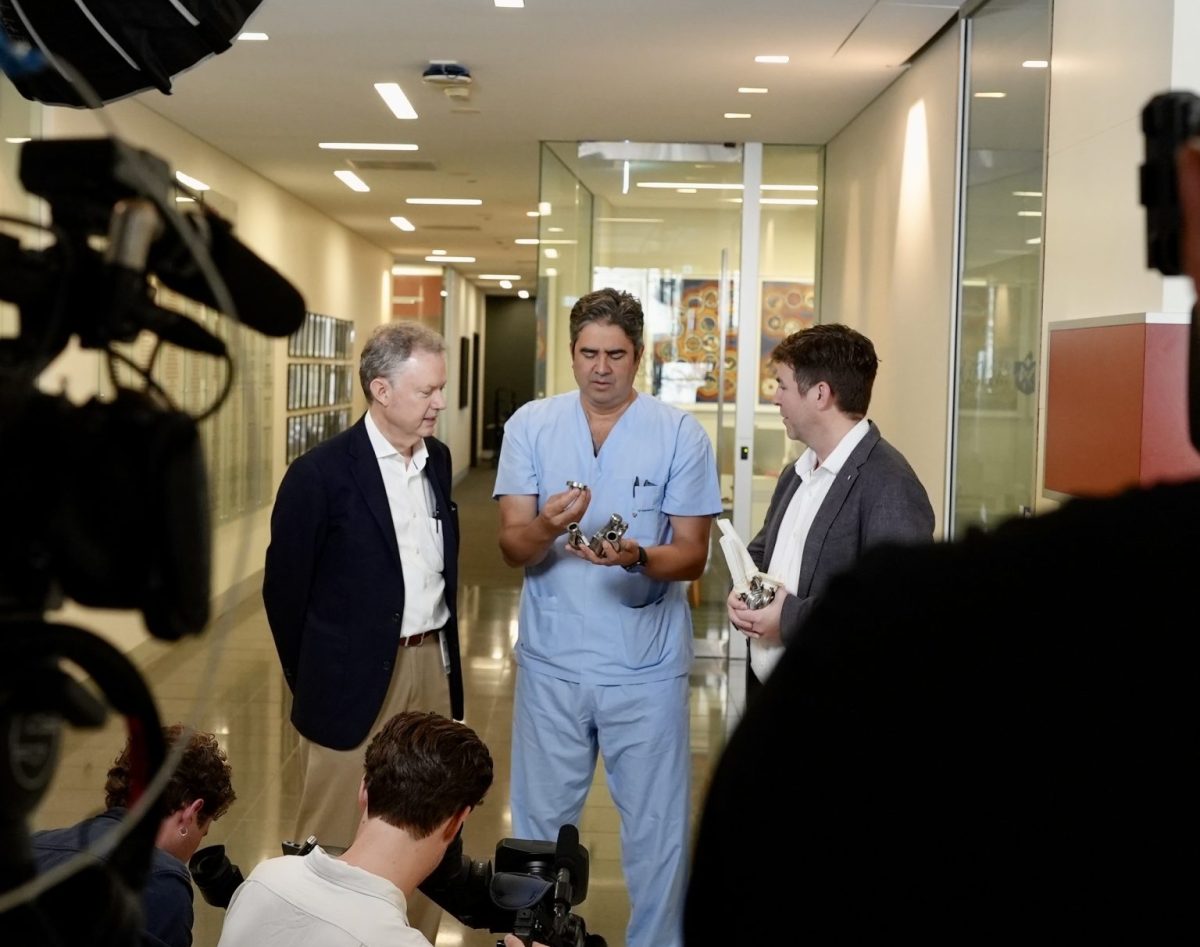

Professor Chris Hayward is a cardiologist with the Heart Failure Transplant Team at St Vincent’s. He is also Jayden’s cardiologist. “Chris Hayward is just, my absolute hero,” says Jayden. “My saviour almighty, literally.”

A bridge to life

It’s hard to reconcile the idea of Jayden lying on life support – his young son saying his final goodbyes – with the strong, vibrant, enthusiastic man that he is today. But in the three weeks between being put into a clinical coma and being taken out of it again, Jayden was surgically fitted with a Left Ventricular Assist Device (L-VAD). A mechanical pump that moves blood around the body on behalf of the heart’s left ventricular. He then lived with this pump for 436 days.

This surgery is a bridging treatment to help waitlist patients stay alive longer in the hope an organ donor can be found. For patients, this waiting for a call is possibly the hardest part. It could be two hours or it could be two years, and all that time they’re wired to a small machine that goes with them everywhere. This is where Prof Haywood and his team are making great advances.

Key Statistics:

- 500,000 Australians living with Heart failure

- 60,000 new heart failure diagnoses every year

- 45,000 deaths from heart failure disease every year

The new L-VADS

For many patients the reality of an external battery pump is confronting. “I was mortified,” said Jayden about his L-VAD, “I’m someone that can’t keep my phone charged and then all of a sudden I’ve got to keep myself charged every four to six hours.” According to Jayden the St Vincent’s team really helped him through it, and in the five years since he had his L-VAD removed, there has been continual improvements. Batteries, as an example, now only need to be charged every 18-20 hours. And research is ongoing.

As head of the Mechanical Circulatory Support lab (MCS), Prof Hayward has some revolutionary trials coming up – and there are three with next generation L-VADS. One is a new design from France, another from Australia and a third has been engineered by Prof Hayward and his team at AMR. “It’s a completely different design,” says Prof Hayward of the leaps they’re making in the L-VAD space. Not only will AMR’s new pump be smaller, more efficient and have even longer lasting batteries, but it will involve less complex surgery, which is good for everyone.

Getting home sooner

Even with the older model, Jayden didn’t let his L-VAD hold him back. In the 456 days before he had his transplant, he ran the City to Surf, did the Seven Bridges Walk and even climbed to the top of Mount Kosiosko. And Jayden says his attitude to recovery was very much influenced by Prof Hayward and his team. “Chris gave me some great advice,” said Jayden, “He said, ‘we don’t give these machines to people who just sit and wait for the phone call. That defeats the purpose. You’re getting your life back. Start doing things and live your life.’”

As a firm believer in getting patients home sooner, Prof Hayward places a lot of importance on translating the learnings from his clinics into new research and then back again to leading edge patient care. “One of the research areas I’m involved in at the moment is looking at new ways to thin blood,” says Prof Hayward, “because when you’ve got metal hanging around in the body there’s a risk of clots forming. And so the clinical trial I’m running is looking at, where blood is clotting in the pumps, how it’s clotting, and which blood thinners will work best without causing any bleeding problems.” Key learnings for getting and keeping patients out of hospital.

I’m someone that can’t keep my phone charged and then all of a sudden I’ve got to keep myself charged.

Jayden Cummins, Heart transplant patient

These patients are in a difficult place and they’re relying on us to help them get out of it.

-Professor Chris Hayward, Clinical Cardiologist

Physiological control

Another research project underway is looking at how the L-VAD pumps modulate blood flow. Currently the L-VAD pumps use a continuous spinning impeller. It keeps the blood pumping consistently, which is good, but it also means the blood flow is the same whether a patient is lying down sleeping or, as was the case with Jayden, climbing a mountain.

This new research, in collaboration with the University of New South Wales, is looking at how L-VADs could respond to the body’s own signals and adjust blood flow according to exertion.

Totally artificial hearts

Of all the upcoming trials, the biggest is the feasibility study of the BiVACOR total artificial heart. It’s a new pump that’s able to replace the entire function of the human heart. Now that it’s been successfully implanted into large animals it’s ready for the first in-human trial.

Phase One trials like these tend to involve a lot of unknowns, so there needs to be a high level of trust between patient and clinician. “What we’ve typically found,” says Prof Hayward, “is that people are generally very willing to be involved. These patients are in a difficult place and they’re relying on us to help get them out of it.”

That was certainly true for Jaden who says, “When the smartest guys on the planet say the safe option is to rip your heart out and put in a new one – damn straight you’re gonna take it.”

The lucky ones

The team at St Vincent’s and AMR have been developing and implanting mechanical heart supports since 1994 and with every new decade comes a new generation of supporters. “You can’t go through an experience like that and come out the same,” says Jayden. “To be given the ultimate gift of life, not just the whole organ donation side of things, but that incredible team at St Vincent’s. There’s no way you can get to the end of that and be the same bloke. It’s impossible. This has absolutely, immeasurably changed me.”

You can’t go through an experience like that and come out the same.

Jayden Cummins, Heart transplant patient

Mechanical Circulatory Support Research Program

Learn more about the Mechanical Circulatory Support Research Program

Artificial Heart – Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute